Make AC Milan Great Again: The Derby Della Madonnina Stakes Are High

Make AC Milan Great Again: The Derby Della Madonnina Stakes Are High

Milan’s path to return to greatness is difficult to navigate, but they may well be on their way.

Milan’s path to return to greatness is difficult to navigate. With a Juventus’ dynasty not going away, any misstep can knock them off the track. Elliott Management Corp. has installed a stable upper management team with experience. They now have to decide who are the fundamental piece they can build the future on. Both coaches and players are under scrutiny.

Milan’s Buildup

Gennaro Gattuso is defying the odds; neither Li nor Leonardo has shown total confidence in his coaching ability. But Milan’s result has been impressive under him. They are third in the league with 11 games to go, in spite of a massive injury crisis. With the Champions League qualification spot within grasp, Gattuso needs to convince Milan’s management that he can lead them back to greatness.

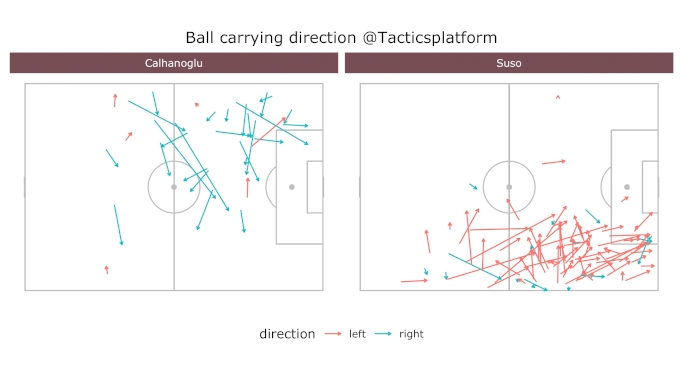

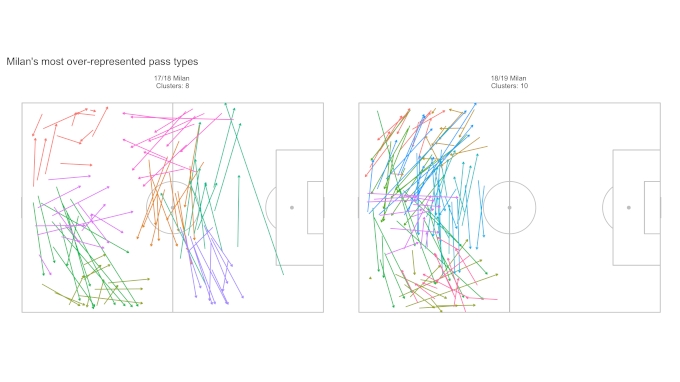

Tactically, Gattuso’s favorite formation is a 4-3-3. Milan’s buildup aims to find Suso or Hakan Calhanoglu close to the final third. Lucas Biglia serves as the link between the defenders and the attacking players. The defenders spread around Gianluigi Donnarumma to facilitate multiple passing lanes toward the Argentinian. Davide Calabria lacks dribbling skill, so Milan often pass through Ricardo Rodriguez on the left. Biglia doesn’t drop too deep to collect the ball so that he can readily connect to the attacking player in the transition. The other two midfielders sometimes rotate with Biglia to displace the opponent’s defense.

The connection between Biglia and Suso transforms Milan from the buildup to an attacking formation.

Franck Kessie will positional exchange with the Spaniard to create space for the latter. If the opponent’s full-back is pulled away from his position, Kessie or the overlapping Davide Calabria can attack that area. Kessie’s position in the final third is strategic.

When he can’t attack an empty pocket, he can still occupy the opponent’s helping defender to prevent him from crowding Suso.

Sometimes Suso can only receive the ball far away from the final third.

In that case a helper, often Biglia, will move close to the Spaniard. If Suso still can’t advance the ball he will reinitiate the attack through the defenders.

The final stage of Milan’s attack has Suso in the final third with Calhanoglu moving across the field to position close to him.

The other central midfield on the opposite side will move into the box to overload the defense. This arrangement gives Suso various options to attack: he can cross/shoot, combine with Calhanoglu in the middle or combine with Kessie and Calabria on the flank.

Milan’s attack on the left differs from that on the right because of their player’s characteristic; Since Giacomo Bonaventura and Calhanoglu can do each other’s job, Milan can rotate their positions frequently on the left. Bonaventura gives Milan’s attack variability.

If the opponent blocks the immediate pass from Donnarumma, he will hit a long ball aiming at Kessie, their only reliable header in the attacking department.

Defensively, Milan use a 4-5-1 / 4-1-4-1.

The lone striker can pressure either one of the opponent’s center backs. Their first confrontation line lies in the middle five players around the half-line. Milan’s on-the-ball defensive pressure is often triggered when the opponent’s central midfielder or the center back controls the ball close to the half-line, ready to make an entry pass. The sided central midfielder, not the inverted wingers, confronts the ball handler. He will run at the opponent from the center to force the ball to the opponent’s full-back. Milan’s winger will then pressure the full-back with the defensive cover provided by the deepest central midfielder. The opponent’s full-back will have a difficult choice to make; the vertical passing lane is too narrow to use while Biglia or Tiemoue Bakayoko is covering the center. Milan can either intercept the ball or force the opponent to re-initiate the attack from the back.

Milan are not a pressing team. Their PPDA is 12.3, the fifth highest in the league, according to Understat. Occasionally, they will hold a high press against a weak side in Serie A. The defensive shape becomes a 4-1-2-3, with the two sided central midfielders supporting the three forwards. But Milan rarely hold a full-court press. The center backs don’t move past the half line. They become quite vulnerable to the long ball because they are too stretched and lost a lot of the second balls. The opponent is often in a great position to counter-attack with only five defenders in front of them.

Bakayoko vs Biglia

Milan’s recent great form coincides with the successful incorporation of Bakayoko; since starting him as the central defensive midfielder to replace the injured Biglia in the 4-3-3, Milan has only lost once in the league.

But Bakayoko can’t be Milan’s fundamental piece in Gattuso’s current system. Milan perform better with Biglia; they created 1.28 and conceded 1.24 Expected Goal (xG) per game with Bakayoko as the central defensive midfielder. When Biglia starts, both areas improves by about 20 percent.

Milan attack better with Biglia than they do with Bakayoko because the Argentinian is a great playmaker while the Frenchman’s offensive game is limited.

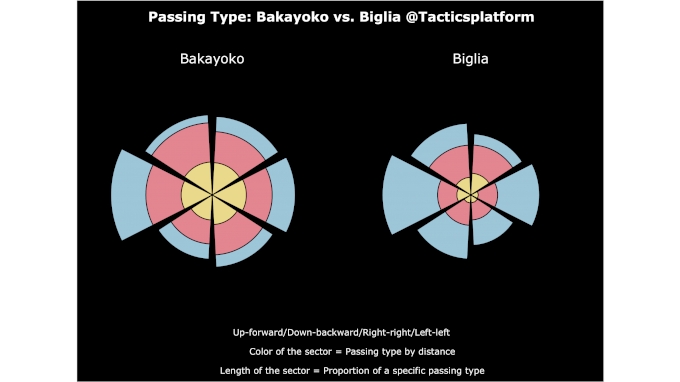

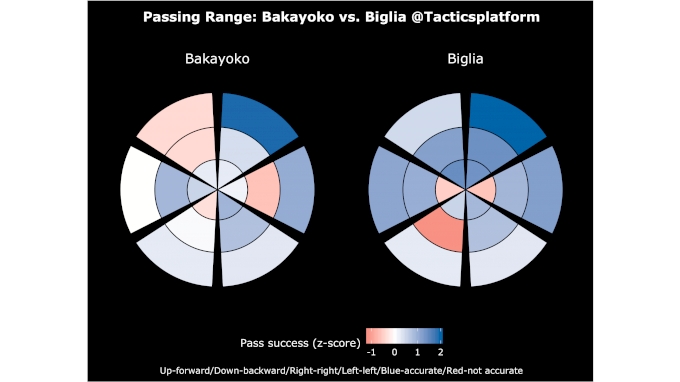

Biglia uses a lot of medium and long passes with excellent accuracy. Bakayoko focuses on the short passes with average accuracy. When rating the overall passing capacity of every central defensive midfielder based on all of the pass types he makes, Biglia and Bakayoko rank in the top eighth percentile and the top 25th percentile in Europe, respectively.

Their passing ranges translate to their individual performance metrics; Biglia’s Expected Goal Buildup is 0.49 per 90 minutes (top 50th percentile for his role), while Bakayoko’s is 0.31 per 90 minutes (bottom 23rd percentile), according to Understat. When calculating how their participation in a possession can influence its outcome, Biglia increases the xG of the possession by 72 percent, putting him in the top 30th percentile among all of the central defensive midfielders in Europe. Bakayoko ranks in the bottom 40th percentile by the same measure. His presence does not affect the quality of the chance that the possession creates. Bakayoko can’t replace Biglia in Gattuso’s attacking setup.

Milan’s improvement in the defense with Biglia is puzzling; by most critics, Bakayoko is a superior defender. His greatest strength is his physical power. You almost have no chance challenging him in a 50-50 duel; in an aerial duel, Bakayoko wins about 63 percent of the headers, putting him in the top 18th percentile among central midfielders in Europe. His physical prowess changes the behavior of the opponent’s attack.

Bakayoko solidifies Milan's low defensive block in the middle pic.twitter.com/QPO1m4olLp

— Cheuk Hei Ho (@Tacticsplatform) February 6, 2019

Bakayoko solidifies the defense in the middle area where he operates. Paradoxically, Milan’s defense worsens on the right flank. Remember how when Milan set up their trap on the flank, the central defensive midfielder has to cover the middle space? Bakayoko has problems reading that situation. He often hesitates to slide to the flank from his middle zone. The tactical awareness of Alessio Romagnoli and Rodriguez compensates for that problem on the left flank, but Mateo Musacchio is often too slow to move out from his position to support Calabria, exposing the defense on the right.

Bakayoko’s characteristic is at odd with Gattuso’s tactics; he is an atypical central defensive midfielder. He can transition quickly if he can run with the ball. But Milan are a possession-dominant team that doesn’t create a lot of transitions, and Bakayoko’s limited passing range doesn’t fit Milan’s attacking scheme. Defensively he is better at competing in the individual duel than reading the space. If they are to keep him, Gattuso needs to design new tactics to better utilizing him.

Milan’s Tactical Limitation

The opponent has also figured out Gattuso’s system; Milan’s main goal of the buildup is to find the inverted winger in the advantageous position. On the right, the opponent has learned that the most effective way to deter Suso is not letting the defender be dragged out when the Spaniard positional exchanges with Kessie. Unlike the similarity of Calhanoglu and Bonaventura, the skill sets of Suso and Kessie are so distinct that the opponent can almost predict what they will do with the ball. Suso often slows down the ball progression because his first instinct is to dribble. The full-back doesn’t need to tackle Suso right away because the ball will stop with the Spaniard, so he can stay back to deny Kessie from attacking his position. As long as the opponent can force Suso to receive the ball away from the final third, Calabria will not be able to overlap. He has to stay back to allow for a passing lane from Suso to facilitate the ball recycling. The opponent will have time to organize the defensive shape.

Milan’s offense has a different problem on the left; Calhanoglu’s dribble isn’t as dangerous as Suso. When he receives the ball with his back to the opponent’s goal, he almost always turns inside to dribble away from the defender.

And because he lacks the sprint that Suso has, he doesn’t consistently get away from his marker. A lot of times he wants to combine with Bonaventura or Paqueta during the positional exchange. But that move is so difficult to make because it requires perfect timing of the movement and a precise, quick one-two. These limitations prevent Rodriguez from overlapping. The Swiss full-back is often criticized for not overlapping enough and making a lot of ridiculous crosses just past the mid-third. But he has no choice; Calhanoglu can’t go left and he can’t carry the ball like Suso. The Spaniard can protect and move the ball, buying time for Calabria to overlap. That condition doesn’t exist when Calhanoglu controls the ball. And without Bonaventura, Calhanoglu poses no threat when he receives the ball in the mid-third. Bonaventura’s injury was such a big blow to Milan that they have only recovered with the arrival of Paqueta.

These problems are systematic issues that Gattuso never solves. You can switch the ball to solve a stubborn defense. Doing that means the switcher and the ball receiver needs to stay far away from each other and explains why Biglia is so important for Milan; he is the only one who can consistently place those passes. But when the ball stalls at the feet of Suso or Calhanoglu, they have no way to get it out. Bonaventura/Kessie will have already moved forward. The full-back has to stay back, and Biglia is too far away to make a timely run to support the inverted winger consistently. The result is all these backward passes to re-initiate the offense that never gets ignited.

You may blame the players or the coach. It is the chicken or the egg; Samu Castillejo hasn’t shown that he should be starting. Fabio Borini is limited. Gonzalo Higuain’s switching had been helpful before the massive injury crisis hit. Krzysztof Piatek and Patrick Cutrone are pure finishers that don’t contribute much in the buildup.

But Gattuso hasn’t shown enough signs he wants to expand Milan’s ways of playing unless they are forced to. A more intensive pressing approach may work; it can take advantage of the physicality of Kessie and Bakayoko and create transitional opportunities to bypass their average offensive game.

The Difficult Path To Greatness

For a new dynasty to rise, the old one has to fall. The Calciopoli creates the Inter dynasty. The economic deterioration creates the current Juventus one. But rarely is one organization so dominant in every way in Serie A. Juventus haven’t shown any signs of slowing down. The condition for Milan to return to the top is not great.

Milan have to be patient, even though that approach doesn’t always work; Inter have done the same way with the backing of Suning Holdings Group in the last two to three years. But as long as you don’t win something important you can’t stay on the course; your best players will want to leave if you aren’t relevant (for example, Ivan Perisic). And if you are unlucky you are gonna have a Mauro Icardi’s situation.

The coexistence of multiple great teams can happen only if they both win something relevant: Juventus/Milan in the early 2000s or Real Madrid/Barcelona in the last five years. Real Madrid might have managed to emerge from Guardiola’s shadow. But they also spent a ton of money. Is anyone in Italy able to repeat that kind of investment?

Milan have a lot of fundamental pieces: Donnarumma just turned 20. Romagnoli is already one of the top two Italian defenders at 24. Kessie and Bonaventura are good enough to get meaningful minutes if they play for a big team. But can Milan keep their best players if they don’t win something relevant in the next few years? Gattuso most likely has maxed out the result he can get with his rigid tactics. Can he evolve? Milan will need major upgrades in the attacking department. Is it achievable given the limitation imposed by the Financial Fair Play? Gattuso has shown that he has talent in coaching. But is it enough to convince Milan’s upper management? There is also the eventual ownership change; no one believes that the Elliott Management Corp. is staying for the long haul, no matter what they have said about developing Milan. The path for Milan to return to greatness is challenging and murky. There are lots of questions but few answers.

This article was written with the aid of InStat Scout by @InStatFootball.

Cheuk He Ho is a scientist during the day who writes about MLS and Serie A during the night. You can find his work at tacticsplatform.com and on Twitter at @Tacticsplatform.